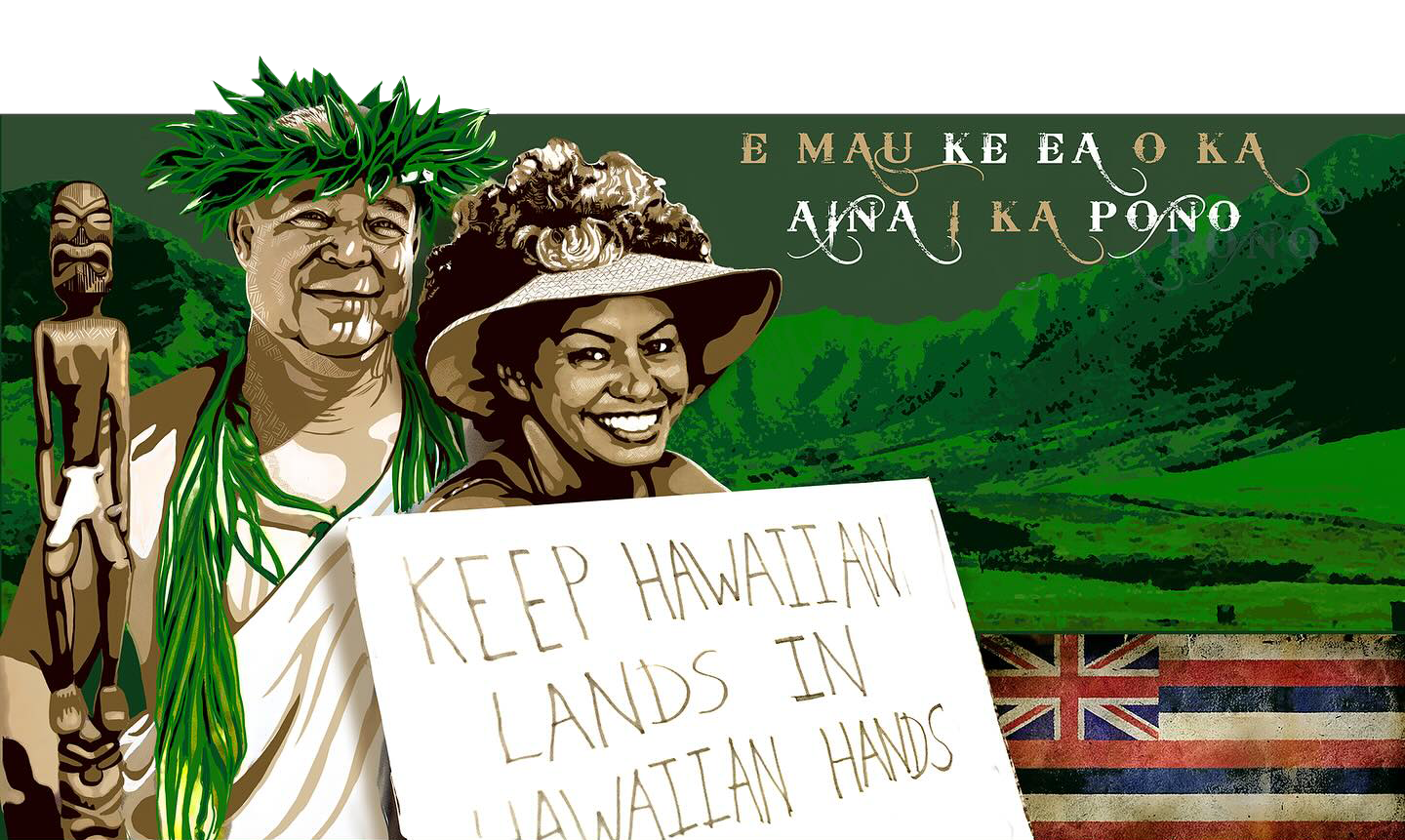

Honoring the life and legacy of Sparky Rodrigues and Leandra Wai of Mālama Mākua

Kū'e Everyday With Sparky Rodrigues

Sparky Rodrigues is a veteran Kanaka Maoli activist from Oʻahu who has been active for decades in grassroots movements for ʻāina, sovereignty, and community wellbeing. Most widely known for his involvement with Mālama Mākua alongside his late wife Leandra Wai, Sparky was also part of the kūpuna line at Mauna Kea and spent twenty years as a video producer with ʻŌlelo Community Media until his retirement in 2016. He lives in Lualualei, where he continues to be an active member of Mālama Mākua, the Waiʻanae Moku Kūpuna Council, and the broader westside community.

Born and raised in Kaimukī, Sparky grew up hiking up to Kaʻau crater and playing with neighborhood kids at his grandmother’s home at the end of the road in Pālolo Valley. When his grandmother moved to Mākaha, he would stay with her during the summers and had his first introduction to Mākua. At his grandmother’s house, the explosions of the bombs at Mākua would wake them from their sleep, shaking the house and rattling the windows. He also remembers tagging along with his father, a mechanic, when he had to service the machinery used for sand-mining at the beaches of Keawaʻula, Mākua, and Mākaha. Mākua always drew his attention.

After spending some time at Los Angeles Community College, Sparky returned to Oʻahu and began working in his father’s auto repair business, before being drafted to fight in the Vietnam War. He returned from Vietnam in 1971. For Sparky, it was a long process grappling with conflicting loyalties of being Hawaiian and being raised American and healing the traumas of war. Like others before and after him, he navigated his own path of healing through reconnecting with ʻāina, becoming a staunch advocate for Hawaiians’ right to access and live in relationship with ʻāina.

Sparky became involved in the struggle at Mākua through his wife, Leandra. In the early ‘90s, she was living at Mākua beach, on her own path of healing. The community living at Mākua beach numbered about 300, mostly Kānaka Maoli, who had found refuge there amid economic dispossession, eviction, medical and mental health issues, and other challenges. Many, including Leandra, found healing at Mākua, and she and Sparky were able to heal their relationship as well. In 1995, Governor Cayetano ordered the eviction of the community at Mākua who were “illegally occupying” public land. (Meanwhile, the U.S. Army continued bombing the valley across the road.) Sparky supported the Mākua Council’s anti-eviction campaign, serving as the communications lead to amplify the community’s message that they were not illegal occupants but a safe and supportive community of Hawaiians living in the last place available to them, just trying to heal themselves and live on the land. Sparky was one of sixteen people arrested during the eventual eviction in 1996, putting himself on the line to stand for Hawaiians’ right to be on the ʻāina.

Amid the anti-eviction struggle, the Mākua Council at the beach joined up with peace and justice activists challenging the Army’s use of Mākua valley for live fire training. These two streams of activism converged to form Mālama Mākua, advocating for the end of military training, the restoration of the valley, and immediate and ongoing access to Mākua for cultural practice. Leandra was a driving force of Mālama Mākua, hosting cultural access in Mākua twice a month, every month, for over a decade. Sparky was also active with Mālama Mākua during this time, stepping in to greater kuleana when Leandra passed on in 2016. He has served as the president of Mālama Mākua and continues to serve as a board member today.

Sparky worked as a producer with ʻŌlelo Community Media for twenty years, using his position there to empower his community to tell their own stories. He and Leandra recorded countless reels of film, documenting the Army’s destructive training, the politicians’ slippery politicking, and their community’s insistence on their kuleana to protect and care for the ʻāina.

With Mālama Mākua and the Waiʻanae Moku Kūpuna Council, Sparky is at the leading edge of community efforts to hold the U.S. military accountable for the harms it has caused, to increase community access to military-held lands, and to advocate for the wellbeing and safety of communities on the West Side. For Sparky, it’s “kūʻē every day.”

He Moʻōlelo O Leandra Wai He Koa Wahine Mana Nui

A Story of Leandra Wai—A Warrior Woman of Great Fortitude

Hānau ʻia i ka pō Lāʻau, lāʻau na iwi, he koa.

Born was (she) on a Lāʻau night, for (her) bones are hard and (she) is fearless.

Said of a bold, fearless person. Lāʻau nights are a group of nights in the lunar month. The days following each of these nights are believed to be good for planting trees. [464]

She was indeed a fierce warrior—a woman of great and sublime spiritual substance—who also held deep knowledge of planting trees, for this was the way of her world. This was her chosen way of balancing assertiveness, resistance, and persistence with pure nurturance. This was how she paved a pathway toward peace when few others dared to stand steadfastly and defiantly in the face of longstanding bureaucratic and political genocide against the spirit and life of native people plucked from their homeland to be callously discarded. This is a brief recounting, a vignette, to present Leandra Wai.

Born in Honolulu and raised in Kalihi, Leandra was a shy quiet girl ridiculed from childhood through puberty and adolescence about her wispy stature. She graduated from Farrington High School in the late 1960s and went on to create a collage of many colors. She was naturally gifted in artistic and aesthetic expression, and utilized her talents to become a precedent setting entrepreneur—only to be usurped by an unscrupulous and misogynistic partner. This experience taught her how to hone her powers of discernment, and alerted her to recognizing and practicing instinctual awareness of people, places, and things. As she progressed in her life journey filled with countless challenges and victories of varying degrees a blessing was bestowed. Leandra met Sparky Rodrigues with whom she agreed to become life partners and helpmates. As cliché as it sounds, the truth is that the rest was history.

Fast forward to the 1980s and 1990s when encampments by protesters, primarily Native Hawaiian, were forcibly evicted from Mākua Beach. Sparky and Leandra were present with their young children. Living on the beach despite having a house in Lualualei was their way of participating in exposing the raw wounds of native people torn from their traditional and generational home lands. In large part, this was about a broken trust agreement between the U.S. Military and the people who called Mākua Valley home until the 1920s and subsequently the 1940s when they were completely and fully unethically and violently evicted. Held as a strategic military training and defensive post since late 1920 to support both World Wars, during martial law the U.S. promised to return Mākua Valley to its original inhabitants six months after the end of the second world war. When Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945 effectively ending the war the clock began ticking. It is still ticking today, 95 years later. Salting the fetid and weeping open wound of the broken trust is the fact that in 1964 the State of Hawaiʻi aided and abetted the ongoing illegal occupation and destruction of the valley. This was wrought through the execution of a heinous $1.00 for 65 year lease agreement allowing the U.S. military’s continued misuse of the land. The lease has an expected expiry date in 2029.

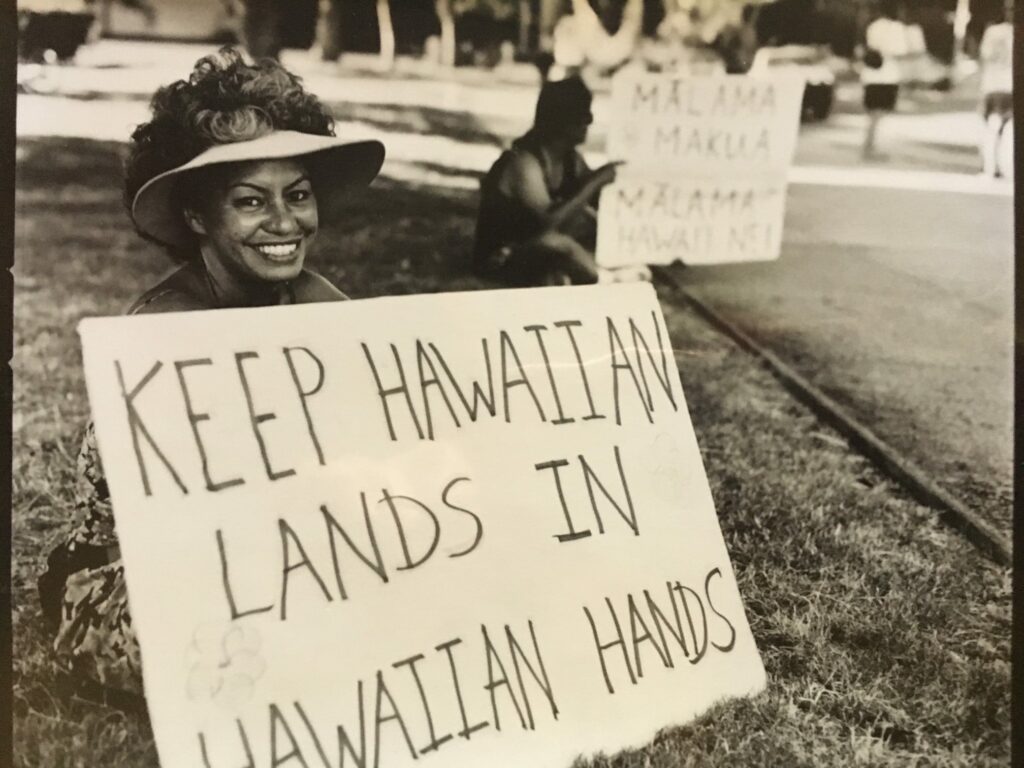

In 1996 following the last eviction of protesters from Mākua, a grassroots coalition of Waiʻanae Coast and other like-minded warriors founded Mālama Mākua, a nonprofit organization led by cultural practitioner Leandra Wai. Under Leandra’s leadership numerous negotiations finally led to the U.S. military acquiescing, thereby permitting Mālama Mākua to lead cultural accesses for the public to view cultural sites lying within the Herbert Pililaʻau live-fire range at the Mākua Military Reservation. Despite live munitions training that left a multitude of unexploded ordnance scattered throughout the valley, the Army was responsible for ensuring safe pathways for participants on these accesses led by Leandra and Mālama Mākua. In 2004, it was adjudicated that live-munitions training would cease. In 2016, Leandra Wai succumbed to illness and passed away peacefully. In 2020, federal legislation introduced by Congressman Kaialiʻi Kanahele entitled the Leandra Wai Act was passed, ensuring the return of the Mākua Military Reservation to the state. Cultural accesses, not regarded as “tours,” persist today as a major part of Leandra’s legacy.

The timeline provided above does little to describe the significance of Leandra’s personal conviction and involvement in the movement to right the wrongs of decades of pain and suffering. There are metaphorical parallels between Leandra’s personal and public personas not generally known by or shared with the public at large. While it is not necessary to unveil every detail of these parallels, the following account will hopefully provide specific and significant insight to the mettle of this Native Hawaiian Warrior Woman of Substance.

Leandra made critical choices in deciding what battles she would wage during her lifetime that would be of meaningful significance for her family, her community, and for her beloved home in the pae ‘aina o Hawaiʻi. She was an extremely sensitive and spiritual woman who was gifted with the ability to openly commune with ʻĀina—all that nourishes—and understood the call of Mākua, her generational parent. Literally walking alone in the darkest of nights as well as under the light of the moon on the pathways within the ahupuaʻa of Mākua, she paid close attention to her parent’s voice. Directed to fight to protect and preserve her parent she learned valuable lessons about protocols and behaviors that would hold and aid her in the work that was to ensue.

In one instance worth recounting, during the beginning of an access into the valley, ever present armed soldiers apparently wanted to express their power and domination over the demure woman whose shoulders were wrapped in pareau, head sporting a floppy brimmed papale. With his rifle held tightly across his chest a young soldier leaned toward Leandra who was facing him barely two feet away, and began barking loudly about the dangers of proceeding into the valley beyond the group’s place of assembly. Placing her hands on her hips, she gazed directly at him, calmly explaining in low tones that she was very familiar with her task at hand, the responsibilities of the liabilities that she bore, and finally concluding with a request for him to kindly get out of her face. Taken aback, the young man’s face reddened beyond crimson and his eyes narrowed, palpably revealing the magnitude of his anger at her rebuke. He shouted again, but unperturbed, Leandra held her ground inquiring as to whether or not she needed to repeat herself, and told him that the access could not be held up any further. After several tense moments that in reality lasted for about a minute or two, his shoulders slumped and he begrudgingly stepped aside, still tightly holding his loaded weapon of war before a woman of peace. The access proceeded as planned.

This little story is shared with the aspiration of making clear her outward fearlessness, and unwillingness to be cast asunder as history retells the bitter stories of loss suffered by native peoples at the hands of others. Know that Leandra was willing to stand her ground, KUʻE, literally, and at all costs—to appear fearless and undaunted, in spite of an inner sense of meekness. She learned, as ʻĀina incarnate as Mother Earth, continued to lead her further in her pro-activism, prioritizing the preservation and perpetuation of the intrinsically symbiotic and reciprocal relationship between humanity and all that feeds and nourishes. She consistently sought to achieve harmony and balance in her own life fraught with very personal and private challenges, and the need to prioritize and recognize the kinds of sacrifices that she would ultimately choose to make. Those include relationships with family members and friends. Who among us today is ready to listen for, to actually hear ʻĀina, and to respond accordingly with purest aloha in the sense of agape love, concern and care. Leandra has left us her legacy of resolve to commit fully—spiritually, emotionally, intellectually, and physically—in the pursuit of justice. She did this through listening, learning, teaching, engaging, piquing awareness, and actively participating in processes that hopefully ensure a more equitable and peaceful future for all concerned.

There is a myriad more moʻōlelo of the life and times of Leandra Wai, however, revelation will come through our shared and ongoing dialogue and work.

Eo mai e ʻĀina Mākua!

Hanohano kou leo nahena

he, he leo makuahine.

E ola nō hoʻi no na ʻōiwi Hawaiʻi.

EA!