Each year at the Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea celebrations in Honolulu we honor two kūpuna aloha ʻāina, one living and one who has passed on.

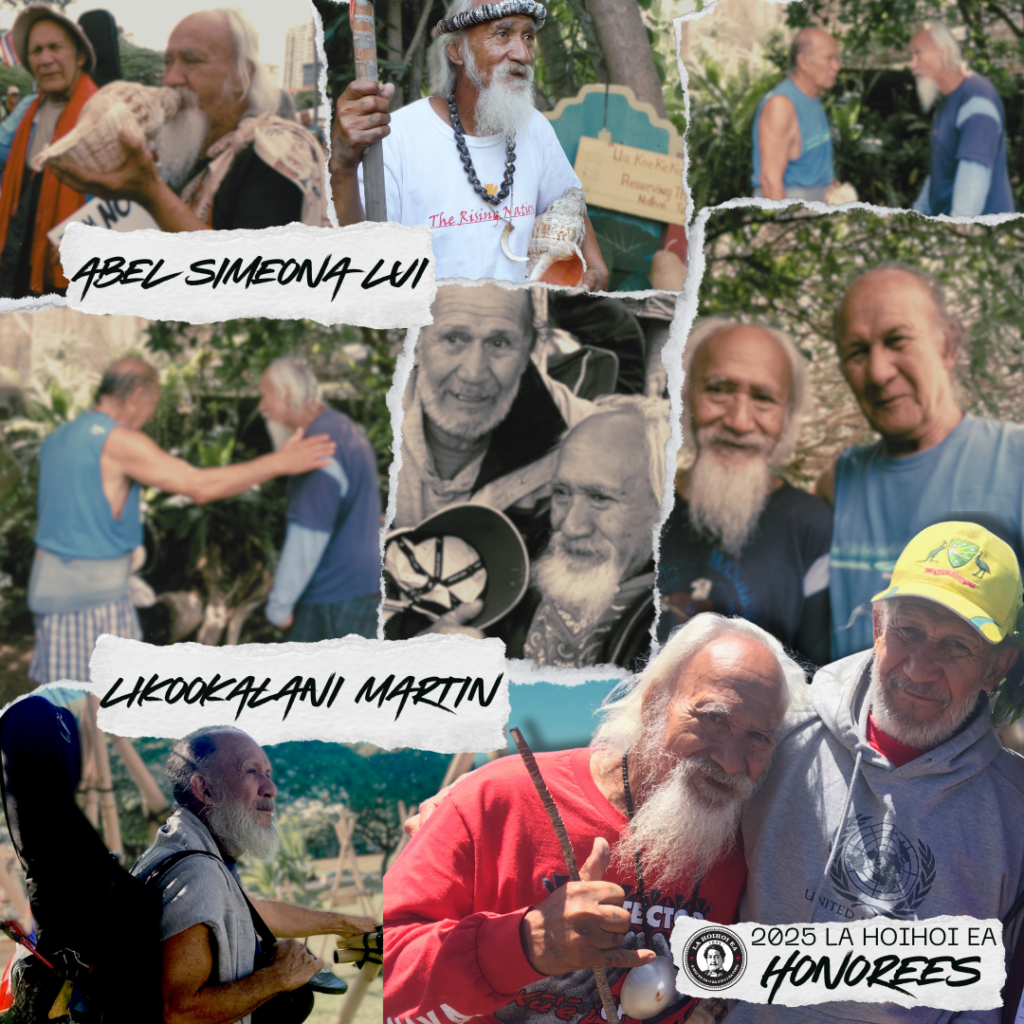

Get to know the incredible honorees for this year's Lā Hoʻi Hoʻi Ea celebration, Likookalani Martin and Abel Simeona Lui. We honor their commitment to aloha ʻāina.

More details coming soon.

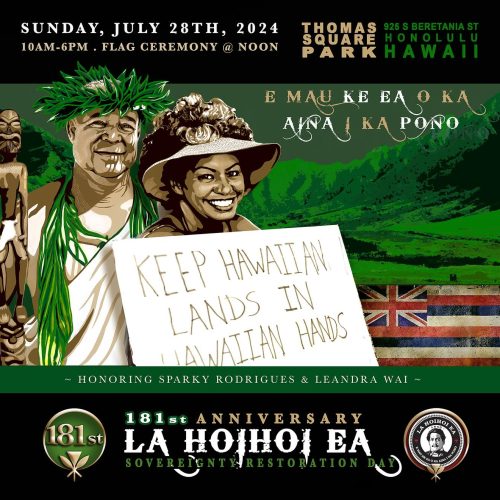

2024 Honorees

Sparky Rodrigues & Leandra Wai

We honor their commitment to Mālama Mākua – click the button below to learn more about their journey as kiaʻi.

2023 Honorees

Puʻuhonua Dennis “Bumpy” Kanahele

& Liwai Kaʻawa

Pu’uhonua Dennis Bumpy Keiki Kanahele is an influential figure in the Hawaiian sovereignty movement and a prominent leader in the pursuit of an independent nation-state for Hawai’i. Kanahele’s journey began in the 1980s when he garnered national attention through his active involvement in the Makapu’u Lighthouse land occupation and a prayer vigil at Iolani Palace, which led to his arrest alongside other participants.

As the Head of State for the newly established Independent & Sovereign Nation State of Hawai’i, Kanahele played a pivotal role in advocating for self-determination and self-governance for Native Hawaiians. He tirelessly participated in state and federal government-sponsored constitutional conventions and legislative processes in pursuit of this objective. Unfortunately, institutional barriers have hindered the realization of justice for Native Hawaiians, despite their persistent efforts.

Through his position as the CEO of Aloha First, a nonprofit organization, Kanahele successfully negotiated a 55-year lease for 45 acres of land in Waimanalo. The lease included a transitional clause that allowed for the transfer of the land to the sovereign Nation of Hawai’i, benefiting Native Hawaiians in their pursuit of independence.

Kanahele’s dedication to aboriginal, native & indigenous rights extend beyond Hawai’i. He serves on the Board of Directors of the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC), actively contributing to its mission of restoring political, economic, social, educational advancement, and just treatment for aboriginal, native and indigenous, peoples worldwide.

In his capacity as President and Head of State for the Nation of Hawai’i, Kanahele is spearheading efforts to establish international treaties of perpetual peace, constant friendship and economic cooperation. With these relationships, we can develop critical infrastructure in areas such as energy, communications, transportation, agriculture, healthcare, and housing through economic cooperation and development. These initiatives particularly prioritize addressing the needs of homeless and houseless communities.

Despite noteworthy accomplishments like securing land and ratifying the Nation of Hawaii Constitution, Native Hawaiians continue to face challenges in their pursuit of justice due to persistent institutional barriers that continue to exist.

Nevertheless, since 1993, Kanahele and the Nation of Hawai’i remain steadfast in their mission to restore the Independent Nation of Hawai’i that was destroyed in 1893. Kanahele continues to promote perpetual Peace, constant Friendship and Aloha throughout America, Europe, and Asia particularly, Malaysia, India, Nepal, and China. Love of Country!

Pu’uhonua D.B.K. Kanahele President & Head of State, Nation of Hawai’i

Liwai Matthew Kalauli Kaawa was a vital part of the Nation of Hawai‘i, headquartered in Waimānalo. Known reverently as “Uncle Liwai” by most people in his community and family, Uncle Liwai was an early leader and kupuna advisor for the Nation and for his first cousin, Puʻuhonua Dennis “Bumpy” Kanahele. Liwai’s father, David, and Bumpy’s father, Benjamin, were brothers from the same mother.

Bumpy shares this moʻolelo about the way Uncle Liwai lived in this Hawaiian movement: “Liwai fervently shared stories of his journey through the water tunnels, mountains on Oʻahu, spiritual encounters, and discussions with leaders like Sam Lono from Haʻikū and others.

Liwai was a handsome, rugged Hawaiian – intimidating at times with a heart of gold. He was all in on the movement. Throughout his life, Liwai engaged wholeheartedly in the journey to restore Hawaiian sovereignty.”

Starting in 1980, during the early years of OHA, Liwai started to become more visible through conducting land title research at the Bureau of Conveyances. During that time, Liwai and others began connecting moʻokūʻauhau, genealogies, into land claims as heirs of the different parcels of land – something unknown and very exciting. This was also a time when some Hawaiians were beginning to feel that there was a possibility of having a Hawaiian government again. Some came to check out what possibilities OHA might create, and others looked beyond OHA.

In 1986, after filing some land claims, Liwai, Bumpy and others decided to try to shut down Sea Life Park, located across from Makapuʻu Beach Park, and to take over operations there for the benefit of the community. The following year, as lineal descendants, they occupied lands around Makapuʻu Lighthouse for a few months, after the Coast Guard declared the land surplus. Kaawa family members filed deeds to claim the land and returned to their ancestral lands. The area was named Kaawa Estates by the ʻohana, with genealogical ties to Queen Kalama and Kamāmalu. In response, police SWAT raided the camp before dawn and arrested 47 people. Uncle Liwai was forced to serve jail time.

On Dec 27, 1988, Liwai posted a legal notice stating “I hereby protest the continuing foreign occupation and rule of the United States of America in my nation Hawaiʻi.” He condemned the 1893 US armed invasion, saying “not once in all their over 93 years of rule has the American nation recognized our people of Hawaiʻi right to determine our own destiny…This American tyranny must end and the reign over the people of Hawaiʻi be returned to the people of Hawaiʻi.” He was ahead of his time.

In June 1992, Liwai was among the thirty-two Hawaiian loyalists arrested at ʻIolani Palace when they peacefully gathered there on Kamehameha Day in order to raise awareness about the upcoming 1993 centennial anniversary of the illegal overthrow. When these kānaka were taken to court, Uncle Liwai asserted that he was a sovereign member of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi.

Throughout 1993, before and after the US Apology Resolution, Liwai worked with Bumpy and others to create the Nation of Hawaiʻi. Bumpy remembers, “Liwai was one of the main pillars, a kupuna advocate for Independence and supporter of the 1995 constitutional convention. Like many of our heroes of the past, we miss him! With guidance from leaders like Liwai Kaawa, from 1993 until now 2023, the Nation of Hawai’i has been on the road to restore our independence.”

VIsit Nation of Hawaii dot org

2022 Honorees

Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu

& Dana Kauai iki Olores

Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu, child of Georgette Moana Mathias and Henry Dai Yau Wong is a longtime advocate and community leader amongst several others that emerged out of the early days of the University of Hawaii at Manoa Center for Hawaiian Studies. She came to Manoa from Kamehameha Schools Kapalama Campus and was born and raised in Liliha-Puunui of Nuuanu on Oahu.

Kumu Hina, for the last 32+ years at the time of this writing, has been involved with many of the issues that have and continue to impact our Lahui Kanaka wherever it may be occurring in the Pae Aina. Her advocacy and voice for the people have made her presence known by many. Some associate her face not only as a staunch voice dedicated to joining other Hawaiian community leaders to champion issues here in her homeland, the mainland of Kanaka. Others also associate her face with being a prominent Mahu (Mahu Haawahine/M2F Transgender) whom asserts an aggressive posturing when it comes to ensuring that the Kanaka perspectives and worldview of sex and gender prevail over such topics in her homeland. Kumu Hina maintains that she is Kanaka, she is Hawaiian first and shall always do what she can to uplift and honor Hawaii and our people, our language, culture and history.

From the time she graduated from high school, she has always found herself in the capacity of teaching and sharing things of our culture and language. Looking back through the years, Kumu Hina went from Kamehameha Schools Performing Arts to UH Manoa Ethnic Studies Hawaiian program, to Leeward Community College Ka Leo Kaiaulu Hawaiian language program (taught around in many community locations), to Ke Ola Mamo Lei Anuenue HIV/AIDS Prevention Education Program Outreach Worker, to the Board President for Kulia Na Mamo non-profit organization improving the lives of the transgender community, to Halau Lokahi Public Charter School where she spent 13 years as the schools’ Director of Culture. She eventually found her way to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs as a Community Advocate and is currently serving our community as the Cultural Ambassador for the Council For Native Hawaiian Advancement.

Her work also includes teaching Kanaka within the incarceration system and currently holds class in the Halawa Correctional Facility located on Oahu. Kumu Hina honors and uplifts not only her own ohana, but also her extended ohana of Niihau and of Tonga as well. These are some of the most influential factors in Kumu Hina’s life and make her who she is today. She also has been a caregiver for many years and for several family members, most currently of which is her mother whom she lives with.

Kumu Hina reminds us to be it and be all about it. She emphasizes that we all possess the capacity for greatness and that we should be the light for someone in our lives. Ola ola ola.

No kuu lahui e haawi pau, a I ola mau.

Dana Kauai iki Olores (1962-2019) is the prodigy of Evelyn and Valeriano Olores and was born in the valley of Waimea, Kauai o Manokalanipo. A myriad of flora both fragrant and non are some of the most memorable images of this Loea Hana Lei. Kauai iki was a graduate of the University of Hawaii at Manoa in Hawaiian Studies and Ethnobotany, a Kumu Hula and a Master Lei Maker.

Her hands wove some of the most exquisite floral pieces in the many styles known to Kanaka, including Lei Wili, Lei Haku, Lei Kui, Lei Hili, Lei Papahi, Lei Humupapa. She wove lei for Kanaka, for Horses, and also made wreaths and arrangements. She could take anything growing by the roadside, forest, sea shoreline, highways and byways and create a masterpiece to wear or sell. Her artistry and creativity completely funded her studies at UH Manoa, provided for her living, and took her around the world.

Kauai Iki was also a Haku Mele and composed many songs along the course of her life. She composed and choreographed many of the chants and dances that her students performed. Kauai iki not only taught in the community at UH Manoa, but also formerly at Kalakaua Intermediate, Farrington High School, and around the world whenever she was asked to teach a workshop or lesson in Lei Making, Hula or Hawaiian culture.

She was very proud of her halau on Oahu and Kauai, named Ka Pa Kanaenae o Kauai Iki and taught Kanaka, Kamaaina and Malihini Haole alike in her classes and never charged a fee for her teachings. Her philosophy was that “the knowledge that was given to me with love and aloha shall be taught in the same manner, and always…ALWAYS free of charge.”

Kauai iki also taught at Kula Aupuni Niihau A Kahelelani Aloha (KANAKA), a Hawaiian focused charter school in Kekaha, Kauai dedicated to the preservation and perpetuation of Niihau island language and culture for Niihau descendants living on Kauai island.

For many years, Kauai iki could be seen offering Mele Oli and Mele Hula at any and all of the events, rallies, demonstrations, protests, marches and anything else that was going on to bring our Lahui Kanaka together. One of the most prominent of these ongoing events is La Hoihoi Ea held annually at Kulaokahua (Thomas Square) in Honolulu, Oahu. She was never one whom wished to take the lead in speaking to people for she would always say that her role as Mahu (Mahu haawahine/M2F Transgender) maintaining vigilance in Pule (prayer) was the most important contribution to be made.

One of the most prominent of Kumu Kauai Iki’s friendships was that of mentor, role model and kua’ana to Kumu Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu. These two prominent Mahu could be seen for many years as they would visit seashore to forest on any island that they were on in search of the kinolau of the traditional Akua of our Lahui Kanaka. These kinolau were gathered and often put into a woven basket to be carried down the road as they chanted unto the ancient entities and ancestors of Hawaii Pae Aina Aloha and invoked their presence into everything that they were a part of. Aloha, Mahalo, Laulima, Kokua, and Kuleana were always a hallmark of being in service to our Lahui.

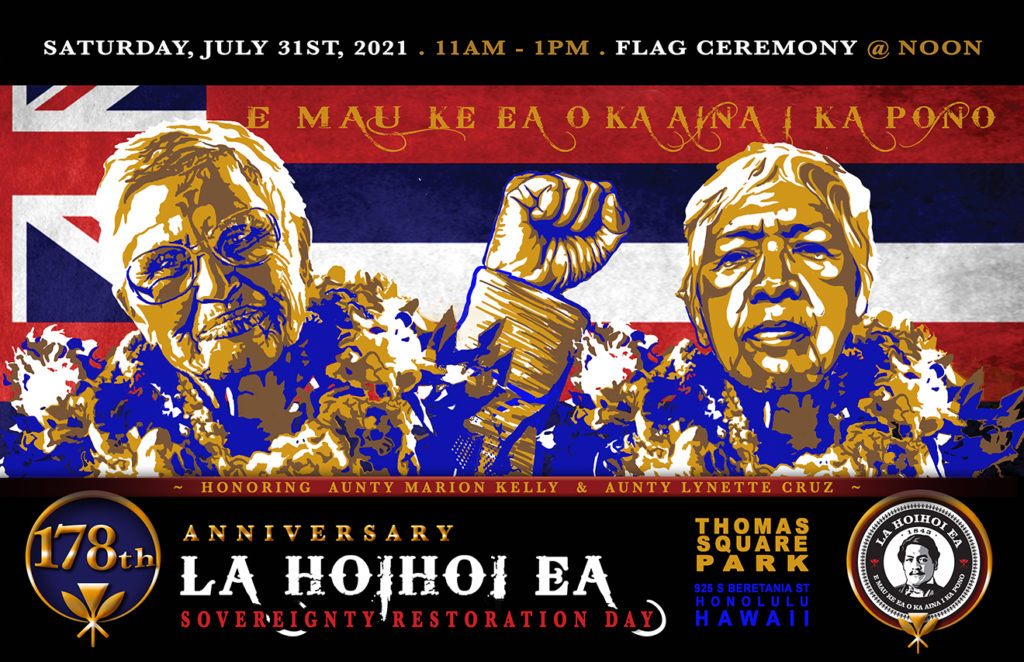

2021 Honorees

Lynette Cruz

&

Marion Kelly

Lynette Hiʻilani Cruz is a revered Kanaka Maoli leader, teacher, activist, organizer and cultural practitioner. Hilo born and Honolulu raised, Aunty Lynette was raised in Kapāhulu. She graduated from Kaimukī High School and began working. Aunty Lynette has worked in countless grassroots community contexts, is a staunch advocate of Hawaiian independence, and has been a steadfast part of the Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea organizing core on Oʻahu. Aunty Lynette has led many social justice organizing efforts and served on a number of boards, ever active in community.

She served as the Oʻahu Island educational coordinator in Sovereignty Education program for Hui Naʻauao for three years in the late 80s and early 90s, the Coordinator of the Ahupuaʻa Action Alliance from ʻ94-ʻ96, a board member and chair for the Hawaiʻi Peoples Fund for 4 years, and so much more. Her many affiliations and projects speak volumes to the tireless work she does for the betterment of our communities.

In the late 1980s, she returned to school, completing a BA in Pacific Island Studies, and then earning her MA and PhD degrees in Anthropology at UH Mānoa. During these years, Aunty Lynette also began teaching at HPU Hawaiʻi Loa College, Kapiʻolani Community College, and Hawaiʻi Pacific University in Anthropology and Pacific Island Studies. She is a constant educator, inside and outside of the classroom, finding every opportunity to share knowledge and build peaceful dialogue. After retiring from teaching at the University level, Aunty Lynette became the poʻo of organizations like Mālama Mākua. She now resides on the west side in Waiʻanae and continues to contribute to community care and organizing, as well as teaching at Leeward Community College. These days, many also know Aunty Lynette as the Poʻo of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina o Ka Lei Maile Aliʻi, an Oʻahu-based organization that honors the life and work of Queen Liliʻuokalani through education and cultural programs related to Hawaiian history. You can see her carrying the names of kūpuna who signed the Kūʻē petitions in protest of annexation.

In 2019 Aunty Lynette helped to create and publish a Native Hawaiian Health and Politics Survey, distributed around ka Pae ʻĀina and especially on the Mauna at Puʻuhuluhulu. The survey was created to better understand needs and issues within our Hawaiian communities. Aunty Lynette has been a tireless beacon of strength and action to all, never seeking glory and always lifting others up before herself. Although “retired,” she is as active as ever. Much of her energy goes toward helping to get kānaka plugged into movements through education and social support. From education, to activism, to organizing, to storytelling, Aunty Lynette remains an example of the resilience, intelligence, and strength that our ancestors embodied every day.

Thankfully we can model ourselves after aloha ʻāina like her and continue their stories.

Marion Anderson Kelly (1919-2011) was a brilliant teacher, tireless activist, and a true example of aloha ʻāina and genuine allyship. Marion was born in Honolulu to Thelma and William-Grieg Anderson, and raised on the Waialua Sugar Plantations. In 1937, she graduated from Roosevelt High School, where she met her husband, John Kelly. Together they became warriors for justice

in Hawaiʻi. While not ethnically Native Hawaiian, she was as an aloha ʻāina.

After Marion graduated from UH Mānoa in 1941, the young couple moved to New York City, where she studied at Columbia University, focusing on sustainable economies and cultures of Indigenous peoples. This sparked her interest in early economic and agricultural models of the Hawaiian people. Her 1956 MA thesis, “Changes in Land Tenure in Hawaiʻi,” worked to prove the actual depth, complexities, and brilliant sustainability of Hawaiian agricultural systems, and

it refuted the ways Hawaiian social and economic systems had been depicted as flawed by Western scholars. Aunty Marion then began a career at the Bishop Museum, where she worked on many anthropological reports and archaeological studies in various places across the Pae ʻĀina and throughout Oceania. She didn’t just write reports and articles; she used this knowledge to fight for the protection of ʻāina. From Lumahaʻi on Kauaʻi to Kaʻū on Hawaiʻi, Aunty Marion fiercely supported protectors of these places, and shed light on the ingenious Poʻe Hawaiʻi

Kahiko who stewarded these lands. The museum fired her after more than 25 years of service, because she refused to minimize the cultural importance of lands and to buckle to developers who preferred half-truths or cover-ups that could grease the wheels on construction projects.

In addition to her professional work, Aunty Marion was a steadfast activist who created, led, and supported many organizations working to bring justice to the people and ʻāina. In 1964, Aunty Marion and Uncle John co-founded Save Our Surf (SOS) to protect Hawaiʻi coastlines from overdevelopment and foreign interests. According to Ed Greevy, “it was Marion that politicized the man. He was crazy about her. She was doing work with the ILWU.” Save Our Surf organized against evictions at Sand Island, Mokauea, Chinatown, Waiāhole, Waikane, and

Kaʻiwi, among many struggles. They worked alongside revolutionary groups fighting for the protection of Hawaiʻi and the liberation of ka Poʻe Hawaiʻi, who had had enough of U.S. military occupation. From humble rallies to massive achievements, like ending plans for highrise hotels directly on the reef at Ala Moana, their work can be seen throughout Hawaiʻi today.

While continuing her anthropological work across the islands, Aunty Marion also began teaching at the University of Hawaiʻi in the mid 60s. She became a driving force in the creation of an Ethnic Studies department at UHM, working alongside other radical, change-seeking educators. Known by her colleagues and students as “a staunch champion of peace and justice for all of humanity,” Aunty Marion has changed the lives of the many she mentored and taught. Aunty Marion continued as a professor of Ethnic Studies, until she retired at the age of 81.

Through her work, dedication, aloha, and strength, Aunty Marion has changed our

understandings of Hawaiian history. She laid foundations for understanding how traditional Hawaiian land systems worked; she supported kiaʻi, mahiʻai, and lawaiʻa. She spoke out against state and corporate efforts to coopt Kānaka and settlers. She reminded us we are brilliant and powerful; and we continue to breath life into the memories she uncovered.

2019 Honorees

Keliʻi William “Skippy” Ioane Jr.

&

Abraham “Puhipau” Ahmad

Keliʻi William “Skippy” Ioane Jr., was born in the fall of 1951 to Kaualililehua Judd of Pālolo, Oʻahu and Keliʻi Ioane Sr., of Keaukaha, Hawaiʻi. He and his five younger siblings, were raised between the one hānau of both parents. While living in Keaukaha, he was influenced by his paternal grandfather, Keliʻikanakaʻole Ioane (Wiley Kanak), who never embraced Christian theology, or western assimilation, despite a subjugated childhood as a ranch-handler in Kapapala, Kaʻū. This had a strong impact on Keliʻi Jr., In school, at a very young age, he found himself unable to conform to the westernized restructuring system.

Keliʻiʻs first exposure to the modern Hawaiian movement was supporting the Deleon ʻOhana at Kūkaʻilimoku village, a forerunner for kānaka maoli land occupation. This inspired him in 1980, to create Kinʻs Landing Village (KLV) located on raw lands in Keaukaha Tract 2 Hawaiian Homelands. Kingʻs Landing was a model of subsistent, off-grid living, for beneficiaries unable to meet the rigid financial requirements of DHHL. During this time, he also made several trips to Kahoʻolawe, where he was the initial builder of the first hale at Hakioawa. These experiences would lead Keliʻi on a path of resistance towards Hawaiian subjugation on all levels. Through his capacity as KLV founder, he led the village as a model for modern-day kānaka occupation through their public legitimization struggles with DHHL. In these efforts the villages’ administration, Mālama Ka ʻĀina, Hana Ka ʻĀina Association (501-C), fosters community outreach, by promoting kānaka occupation and culture revitalization.

Keliʻi was raised by Hawaiian musicians, and grew up around a time when revolutionary music united minority groups in resistance towards US domination. Soon, Keliʻi found himself inspired to write Hawaiian-revolutionary music. He and 4 friends in 1998, began a revolutionary and Hawaiian music band called, “Big Island Conspiracy.” Like it had never been heard before, on a very truthful and raw level, the group sang about the sovereignty movement, colonial manipulation, illegal annexation, Christian domination, and historical trauma. They also sang about, aloha ʻāina patriotism, and its decriminalization, among traditional Hawaiian mele as well. Through their music, they promoted important revolutionary theories such as, “We The Evidence, We Not The Crime!” Keliʻi, was arrested during both efforts to protect Mauna Kea, and has vowed to continue in the movement as a kūpuna front-line protector. His current project is the creation of a Big Island KANAKA Caucus Convention in 2020.

Abraham “Puhipau” Ahmad (1937 – 2016) was a Hawaiian Kingdom patriot and documentary filmmaker who dedicated his life to enlightening himself, his people and the world about Hawaiian history, sovereignty, and aloha ‘āina. Born in Hilo, Abe (as he was called then) described himself a “hapa-stinian,” one of four children of a Palestinian-Hawaiian union. He graduated from the Kamehameha Schools, class of 1955 and then spent a decade as a seaman, traveling from California to Vietnam and to South America. During this time he became critical of imperialism, writing: “In many of the Latin American ports where we docked I saw a lot of guns. Local resources were being ripped off and governments had to use martial law to protect the thieves.”

When he returned home in 1970, Ahmad frequented the growing urban fishing community at Sand Island, and he eventually took up residence there. He made regular deliveries of ice to Sand Island residents to help with food storage, and they selected him as a spokesperson when they were fighting eviction by the settler state. During this struggle, he took for himself the name Puhipau, a name found in his family’s genealogy. He explained: “puhi pau means blown away, completely burned. Puhi pau ʻia nā mea huna, all the secrets were revealed.” His ancestor, Susanna Puhipau, can be found on the first page of the Kūʻē petitions, protesting the US annexation of Hawaiʻi, and he carried this legacy through his life’s work.

Puhipau turned his attention to educating through the medium of video, and he formed one of the most prolific and widely known documentary film teams in Hawai‘i, Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina, (“the eyes of the land”) with Joan Lander.

Over the next four decades, Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina productions covered critical issues in Hawaiʻi and Oceania, including the nuclearization of the region, the bombing of Kahoʻolawe, the theft of water from Hawai‘i’s streams, the destruction of Pele’s rainforest domain by geothermal development, the desecration of the summit of Mauna Kea, and the unearting of burial sites on Maui. They have documented movements fighting evictions at Mākua, Waimea, Waimānalo and Ka Lae; protecting Hāloa (kalo/taro); restoring traditional ahupua‘a systems; asserting the history and existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom; and celebrating the arts, music and dance of Hawaiʻi and the Pacific. Puhipau represented his work in international film festivals from Yamagata to Berlin, New York City to Aotearoa. Local and international television networks have featured Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina productions, and their documentaries continue to be used in educational institutions worldwide.

Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina has been honored by the Hawai‘i House of Representatives, Hawaiian Civic Clubs, the Hawai‘i Film Office, Pacific Islanders in Communications, Hawai‘i People’s Fund, Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, and MAMo. In 2017—a year after passing from this earthly realm—OHA recognized Puhipau among “Nā Mamo Makamae o ka Po‘e Hawai‘i” (Living Treasure of the Hawaiian People). Ironically, Puhipau had never been a fan of the kind of pseudo-sovereignty that OHA represented. In fact, in 1980 Puhipau ran for a seat on OHA’s board, promising that if he were to be elected he would work to do away with the agency. This is the spirit of defiant aloha ‘āina and steadfast commitment to Hawaiian independence that he embodied.

2018 Honorees

Moanikeʻala Akaka

& Nani Rogers

Moanikeʻala Akaka (1944 – 2017) traced what she called the “beginning of the Hawaiian Movement for justice” back to the Kalama Valley struggle in 1970, where she was activated, organizing against evictions. Aunty Moani was involved from earliest days of the movement as a founding member of Kōkua Hawaiʻi, the PKO, and Ka Lāhui Hawaiʻi. Once she moved to Hawai‘i island, she became central to several land struggles there, including the Hilo Airport blockade and the protection of Wao Kele o Puna. For years, she and her husband, Tomas Belsky, published a newspaper titled, Aloha ʻĀina, which aimed to educate residents and visitors about Hawaiian and international political issues. Aunty Moani served 12 years as an Office of Hawaiian Affairs trustee: “I never wanted to sit on my ass in an office and do nothing,” she said. And she didn’t. She raised hell about political corruption and mismanagement. Fiery and fearless, Aunty Moani would go toe-to-toe with anyone in political and intellectual battle. Of the contributions and contentions she made at OHA, she looked most proudly upon the years she spent negotiating with the state on the back rents due to OHA for the so-called “ceded lands”—the seized lands of the Hawaiian Kingdom. She was instrumental in securing over $100 million dollars in trust land revenues toward the betterment of Native Hawaiians. Her work protecting lands continued well after her years at OHA were done in 1996. She was always a fierce advocate of peace, demilitarization and anti-nuclearization in Hawai‘i and the Pacific. In April 2015, Aunty Moani was arrested on Mauna a Wākea for resisting the construction of the Thirty-Meter Telescope (TMT). She was seventy at the time.

Nani Rogers was born on September 8, 1939 in Kapaʻa, Kauaʻi. As an ʻōpio Nani found her way to the epicenter of a changing tide on Oʻahu. She attended Kamehameha while living with her aunt on Kukui Street downtown, where the Territorial government was making way for businesses, buildings and ill-conceived schemes of domination. After high school, Nani became a hula dancer under the legendary Kumu Hula Maiki Aiu and toured the Midwest with the Hilo Hawaiians for two years. For the past three decades, Aunty Nani has brought strength and grace to even the most contentious of struggles. She answered Ka Lāhui Hawaiʻi’s call to engage with the State Legislature on issues affecting Kanaka Maoli rights and lands. Back in the days when sovereignty was considered a pipe dream, Aunty Nani became a Ka Lāhui citizen and served as Poʻo of the Kauaʻi caucus. Armed with a new understanding of Hawaiian history and the inner workings of Hawaiʻi government, Nani served tirelessly with KLH for over a decade. Then her notion of ea began to shift: “I realized that a nation-within-a-nation model was quasi-sovereignty, and that total independence was the only way to free our people and nation.” A fierce supporter of Hawaiian independence, she exemplifies the struggle of her island of Kaua‘i. For example, she remained a faithful resident at the three-month vigil to protect ʻiwi kūpuna at Naue when a developer began construction of a luxury home. Between April and June 2008, she was always present at the site of disinterment and mindful of the ʻaumākua whose bones she safeguarded. For many years, she broadcasted her sweet leo from Hanalei each week on KKCR community radio. She continues in the footsteps of her ancestors from the ʻāina where she came into this world and has consistently brought the strength of her ancestors to our Ea movement.

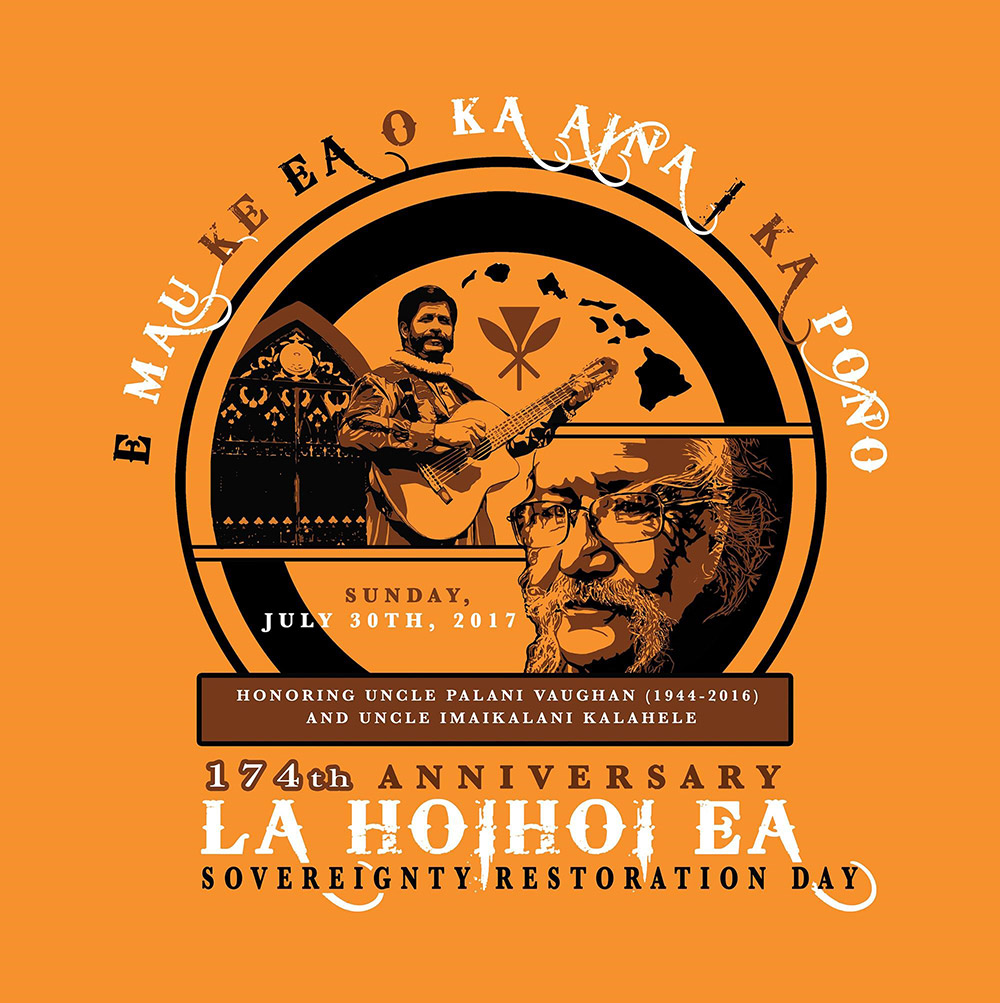

2017 Honorees

‘Īmaikalani Kalāhele

& Palani Vaughan

‘Īmaikalani Kalāhele, aka Uncle Snake, is an aloha ʻāina, a father, grandfather, poet, artist, and musician whose work has appeared in numerous books, buildings and communities. He is one of the co-founders of the contemporary celebrations of ka Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea and for many years led the ‘awa ceremony opening the festivities. As a poet, his work appears in anthologies of Hawaiian literature and art, such as Mālama: Hawaiian Land and Water (1985) and ʻŌiwi: A Native Hawaiian Journal. His book, Kalahele (2002), collected his poetry and art in a polyphonic performance that mixed Hawaiian, Pidgin (Hawaiian Creole), and English. Reviewing the book, Papuan poet Steven Winduo described Kalahele as an artist and poet who “mediates between ancestral knowledge and modern influences in a lace of art and poetry that floats on the currents of the Pacific, across the islands and in space.” As a visual artist, Uncle Snake’s works bring life to our akua, aliʻi and philosophies. For example, he is the illustrator of a 12-book series for young readers about the life of ka mōʻī Kamehameha I, entitled Kana’iaupuni. Uncle Snake is truly a multi-media creator who continues to use his talents to bring light to the struggles of our people. You can hear some of his music and poetry collaborations at http://www.mokakilounge.org/

Palani Vaughan (1944-2016) was a Patriot of Hawaiʻi. He was steadfastly passionate about Hawaiʻi, our Ali’i, culture, mele, kūpuna, nā ʻōiwi and our Lāhui’s demand for sovereignty and making things pono. A central figure in the Hawaiian Renaissance, Uncle Palani is perhaps best known as a pathbreaking Hawaiian musician who remedied racist representations of King Kalākaua through his research, his music and even through the way Uncle Palani carried himself. Best known for his four albums honoring King David Kalākaua, he formed the “King’s Own” and he studied, composed, published, recorded, and performed tributes to our mōʻī. He prioritized using his music to honor our monarchy and to educate people about it, rather than chasing commercial success. Uncle Palani was inducted into the Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame in 2008. When he joined the ancestors in 2016, his ‘ohana said: “He was a great teacher nurtured by great teachers, and touched so many with his music, his words, his spirit. He was selfless, haʻahaʻa, believed in prayer, loved and cared for our kūpuna. He listened to their voices on the wind, shared their lessons, and ensured they will always be heard and carried on.”

According to his family, he loved the palace and always made time to clean the graves there. While he has always been well known for his music, he worked very quietly and steadily on his own for our nation and for his family in unseen ways. We reaffirm his commitment to his mo’opuna and to all ‘Ohana Hawaiʻi. His family says he would want us to remember that “he was but one soldier in a Hui of Na Koa holding the Torch of Righteousness for all future generations. E Kū Ha’aheo! Eō!”

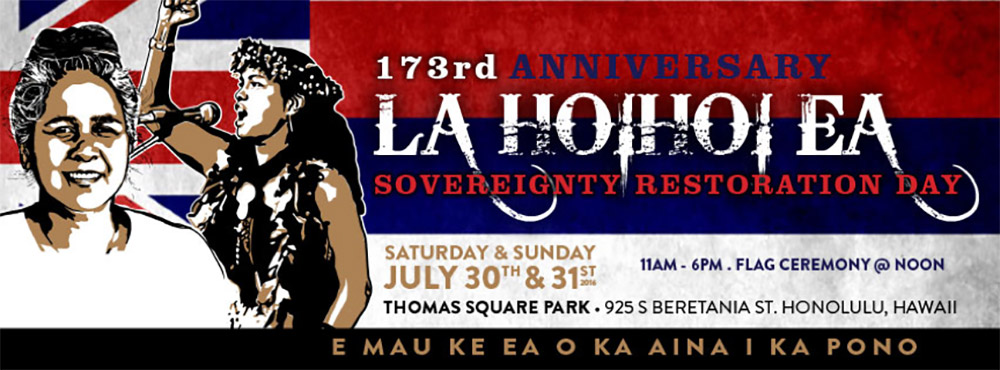

2016 Honorees

Dr. Haunani-Kay Trask

& Judith Keonaona Flores Napoleon

Dr. Haunani-Kay Trask is one of the most influential Hawaiian nationalists of our time. Born to a political family in 1949, Haunani developed her legendary oratory skill reciting her father’s legal arguments from a young age. She graduated from Kamehameha Schools in 1967, entering college at the height of the Black Power and anti-war movements on the US continent. She studied radical feminism and while finishing her doctoral dissertation, returned home in 1978 to enter Hawaiian politics by working with the Protect Kahoʻolawe Fund. After completing her PhD in political science through the University of Wisconsin-Madison, she became a professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. During this time she founded the political news and analysis TV show, “First Friday.” Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies could be described as “the house that HKT built,” as she led the charge to have the Hawaiian Studies building constructed and to open positions for more Hawaiian Studies faculty. Throughout all this work on the ground, Trask also published four books, both academic and poetic. Her influence extends far beyond Hawai‘i; Dr. Trask is perhaps the most internationally-recognized Hawaiian scholar, known around the world for her fierce critiques of racism, colonialism and imperialism. She saw herself first and foremost as an educator, and she encouraged countless Hawaiian students to pursue higher degrees to advance the Hawaiian nation. The legacy of her intellectual and activist work is immeasurable, and it lives on all of us who continue to give breath to her powerful words: “We are not American! We are not American! We are not American! Say it in your heart. Say it in your sleep. We are not American! We will die as Hawaiians. We will never be Americans.”

Judith Keonaona Flores Napoleon (July 2, 1934 – July 27, 1987), One of the unsung leaders of the early Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana and a dedicated grassroots organizer, Auntie Judy Napoleon was a native of Molokaʻi who dedicated her life to serving her lāhui and ʻāina. She was born as Judith Keonaona Flores on July 2, 1934 in Hoʻolehua to John Ko’omoa Flores and Louisa Punanaokamanuehaile (Rosa) Flores. The fourteenth of seventeen children, Judy spent her young life growing up on Molokaʻi and later graduated from Sacred Hearts Academy in 1952. While raising her four children, Judy loved the work that she did at Queen Liliʻuokalani Children’s Center on Molokaʻi, serving families of her beloved island. In addition to the kuleana she carried for her ʻohana and her job, Aunty Judy’s life’s passion was protecting and preserving land and native rights. Her involvement and leadership in organizations like Hui Alaloa, Protect Kahoʻolawe ‘Ohana, Mālama Manaʻe, Kaiaka Rock and many others led some on Molokaʻi to describe her as “the mother of the grassroots native Hawaiian movement.” She often held strategy meetings at her family home in Kamiloloa, Molokaʻi. Judy inspired others to educate themselves about the issues and get involved. She urged kānaka, “If you have struggles in your backyard, take care of them. Don’t wait for somebody else to come and tell you what to do. Go out there at do it.”

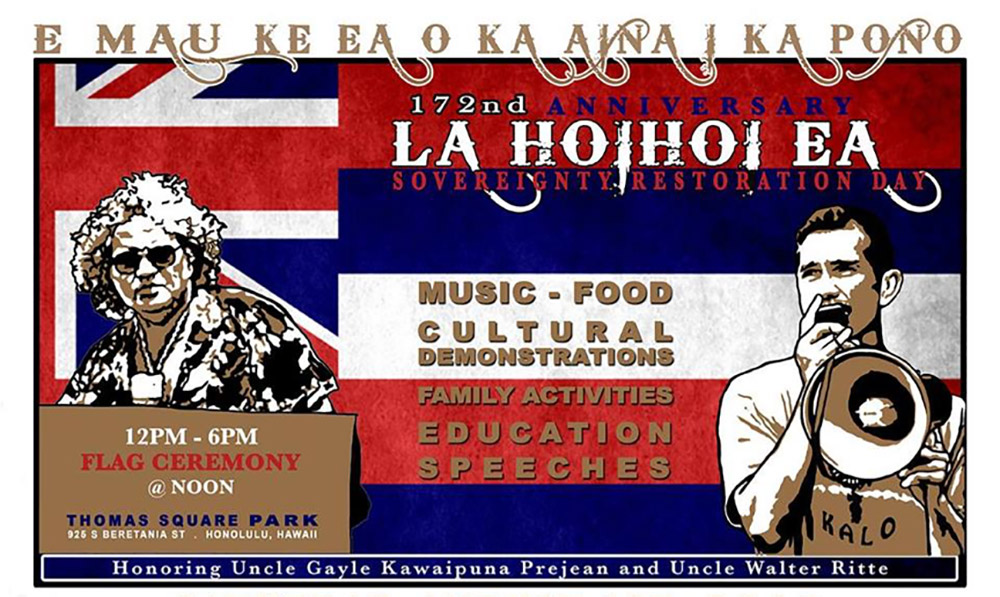

2015 Honorees

Walter Ritte Jr.

& Gayle Kawaipuna Prejean

Walter Ritte Jr., has been a leader of aloha ʻāina movements for four decades. As a native of Molokaʻi, he was initially involved in Hui Alaloa, which fought to maintain Hawaiian access rights for subsistence and cultural practices. He then became one of early warriors involved in resisting the US Navy’s bombing of Kahoʻolawe. Walter and eight others made the first landing on the island Kahoʻolawe on January 4, 1976. He returned less than two weeks later with his wife, Loretta, and sister, Scarlet. The following year, he and Richard Sawyer made the longest of the 1970s protest landings on the island. Walter served in the 1978 Hawaii State Constitutional Convention and was also one of the first elected trustees to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. His courage in protecting Kanaka Maoli relationships to ʻāina continues. Walter has led the struggles against the genetic modification of Hāloa—the elder sibling of Kanaka. Most recently, he has stood beside other protectors on both Mauna a Wākea and Haleakalā. And he has fought numerous battles to protect his home island. He is the founder of Hui o Kuapā, an organization that works to restore ancestral fishponds. He lives the values of aloha ʻāina as a hunter, a caretaker of Keawanui fishpond, an educator, a father and grandfather.

Gayle Kawaipuna Prejean (April 14, 1943 – April 14, 1992) was a Hawaiian nationalist, activist and advocate. Prejean was founder of the Hawaiian Coalition of Native Claims, now known as the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation. A pioneer of the sovereignty movement during the 1970s, Prejean was one of the first voices to advocate for Kanaka Maoli independence at the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland. He was one of the nine people who made the first landing to stop the bombing of the island of Kahoʻolawe by the U.S. Navy in 1976. Prejean was known for his music and “stand-up” comedy as well as for his unrelenting criticism of the U.S. military in Hawaiʻi. It was Kawaipuna Prejean who originally proposed convening the 1993 Peoples International Tribunal, Ka Hoʻokolokolonui Kanaka Maoli, which was carried out after his death. Kawaipuna Prejean died on his 49th birthday. He had been fighting to stop the construction of the H-3, which destroyed many ancient Hawaiian sites and substantially impacted native species on the island of Oʻahu.

2014 Honorees

Terrilee Keko‘olani-Raymond

& Peggy Haʻo-Ross

Terrilee Keko‘olani-Raymond has been a peace and demilitarization activist since she was in high school at Sacred Hearts Academy in Honolulu in the late 1960s. A Kanaka from Kaimukī, who also spent many of her childhood years in the Bay Area, Aunty Terri’s fifty years (and counting) of activism is motivated by an abiding love for her people and her island home. As comfortable at the back of a crowd as with a bullhorn at the front, Aunty Terri is a humble leader who has been a mentor to many young people—Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian—in independence and demilitarization movements in Hawai‘i and beyond.

A student activist in Ethnic Studies at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in the mid-1970s, Aunty Terri really developed her organizing skills through supporting the Waiāhole-Waikāne Community Association against eviction. In that work she became connected with Kaho‘olawe and volunteered to be on the fifth landing of the island in 1977, along with a dozen other aloha ʻāina. Her activism in the 1990s and onward turned squarely toward Hawaiian sovereignty and continued to emphasize demilitarization. You could often find her at the Thursday night hālāwai at Uncle Kekuni Blaisdell’s house in Nu‘uanu. She and Papa Soli Nīheu—her long-time comrade in struggle—would sometimes bicker like an old married couple, without one iota of respect or love lost between them. In this way, they taught the young people in the room the importance of face-to-face dialogue and struggle with one another. They showed how healthy communities and organizers have to tell each other their own truths, even when it is difficult. Aunty Terri has always lifted up youth leaders and made space for them at meetings, at actions, at debriefs. Whether in strategy sessions or casual conversation, she insists upon careful political analysis, as well as upon cultivating relationships of solidarity in Hawai‘i and abroad. Her work has been done through various organizations, especially Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific; Hawai‘i Peace and Justice (formerly the American Friends Service Committee); Women’s Voices, Women Speak; MANA movement; and the De-Tours she has co-led with Kyle Kajihiro, as part of Hawai‘i Peace and Justice, for many years. Aunty Terri’s international demilitarization networking has resulted in linkages between Hawai‘i-based activists with counterparts in Guåhan, Okinawa, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, among others. Her chapter illustrates the capaciousness of her love and commitment to justice for Hawaiians and many others.

For more of Aunty Terri’s life story in her own words, see the book Nā Wāhine Koa: Hawaiian Women for Sovereignty and Demilitarization.

Peggy Haʻo-Ross

Peggy Haʻo-Ross, a full-blooded Hawaiʻi, was born April 14, 1922 and passed away on February 9, 2008. Many considered her a “Mother” of the 20th-century Hawaiian Sovereignty movement, one of the earliest voices for Hawaiian independence in the 1970s. After receiving a spiritual message in 1970 to return to Hawaiʻi, she came home with her beloved husband, Fredrick D. Ross, after living in Idaho and Oregon for nineteen years. In 1972, she founded the ʻOhana o Hawaiʻi. She believed that building the ʻOhana foundation required truth, prayer, and forgiveness.

From 1971-1973, Peggy organized the “Hoʻoponopono-Kūʻauhau” workshops on genealogy, conducted throughout the four major islands with the purpose of gathering Kānaka ʻŌiwi o Hawaiʻi. Many had lost contact with their families, others had no idea who their families were. In 1973, she confronted outgoing Governor John Burns and incoming Governor George Ariyoshi for the derelict and shameful negligence in not providing funds or a safe place to house Hawaiian historical records. She found records wet and falling apart in an underground bunker within the State Archives. She sought to protect invaluable moʻolelo of our past, vital birth records, and evidence of our people’s plight and existence.

Peggy said, “Hawaiʻi is a sleeping giant that needs to be awakened.” On April 14, 1973, the ʻOhana o Hawaiʻi filed a “Declaration of Independence” to US President Richard M. Nixon. The ʻOhana o Hawaiʻi demanded a hearing for the criminal negligence that was going on in Hawaiʻi; however, President Nixon gave no response.

On February 14, 1974, Peggy Haʻo-Ross filed suit (Civil No. 74-33) against the United States of America for $5 trillion. This followed the dismissal of a $300 billion lawsuit in the Ninth Circuit of Appeals in 1973, when members of the ALOHA Association were seeking reparations from the US Congress. Haʻo-Ross said that the United States had conspired to deprive her: (a) right “to be a valid person”; (b) the right to her heritage, culture and identity; (c) the right of sovereignty in and over the Hawaiian islands; (d) 4.5 million acres, the whole of the Hawaiian Islands; and (e) the right of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”. The two civil suits were dismissed. However, through her pursuit of this case, she concluded that the US legal system did not protect the human rights of the Hawaiʻi People, particularly concerning the wrongful annexation of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi.

As the spiritual leader of the ʻOhana o Hawaii, in 1976 Peggy Haʻo Ross warned that the United States would be afflicted with economic disability if they “did not heed God’s warning to restore the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi” to the kānaka ʻōiwi o Hawaiʻi. On April 14, 1978, the ʻOhana offered a “Declaration of Intent” on the grounds of the ʻIolani Palace: “We realize that we are the personally unique, spiritually equal Sons and Daughters to the Living-God of ALOHA.” The ʻOhana claimed dominion of the Hawaiian islands.

Later that same year, as a Kahuna Pule Peggy helped lead a peaceful procession to occupy the Hilo Airport runway. The protest raised attention about the continued breach of the Department of Hawaiian Homelands of their trust responsibilities to Native Hawaiians, leasing lands to non-Hawaiians for next to nothing, while beneficiaries were dying homeless on the waiting list. At the end of Lyman Avenue, where Keaukaha Homestead meets the tarmac of the airport, stood a fence fronting the runway. This fence was wrapped with two large chains from each side and attached to the center by a large lock. Kānaka in white kīhei stood in the front of the gate, watched by plain-clothed policemen amongst them. Kahuna Peggy commanded those in front of the gate to place their hands on it. Those behind placed their hands on the shoulders of those fronting them, making a human web. Kahuna Peggy began to oli. Some say that a bright light and three loud thunderous cracks were heard. The large chain links at three main points of the gate broke. As people laid the gate down respectfully, just beyond the fence, camouflaged soldiers rose with rifles and bayonets aimed at the Kānaka. The people in malo and kikepa began singing “Hawaiʻi Aloha.”

The National Guard had been called in to assist local police. The first platoon were mostly Hawaiians, who had to stand face-to-face with the demonstrators. One of the guardsmen threw off his helmet in despair at the situation and left the line, torn apart that it was Hawaiians facing Hawaiians. Peggy called for a prayer, and the first platoon departed with a blessing and in peace. However, a second platoon described as “foreign mercenaries” followed, and their demeanor was markedly different. They charged with long batons towards the peaceful protesters. Several struggles ensued, some of the peaceful protestors volunteered to take arrest, and Governor Ariyoshi called off the attack. Participants were eventually released without charges from the State and US Federal governments. They successfully called attention to the issue of the Hawaiian homelands “broken trust.” For Peggy, the demonstration was also evidence of the power of her Akua, a warning that “those who seek to harm, injure, or murder the koko poʻe o Hawaiʻi will face God’s wrath.”

On October 30, 1980, the ʻOhana o Hawaiʻi filed a petition for Independence with the International Court of Justice at The Hague, Netherlands. The Traditional Elders of the ʻOhana contended that the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi never ceased to exist and is the legal government authority of the lands and people of the Hawaiian archipelago. Their intention was to secure the rights of the poʻe Hawaiʻi in their pursuit of sovereignty and independence, claiming the entire archipelago as its domain. Documentation was filed at the Hague Peace Palace and at the Palace of Nations archives in Geneva, Switzerland.

Peggy Haʻo-Ross said, “All nations of the world are represented in my ‘ohana. My children are intermarried to all different races and nationalities. I have grand-children who are Hawaiian-Filipino, Hawaiian-Japanese, Hawaiian-Portuguese, Hawaiian-Cherokee, Hawaiian-Haitian, and Hawaiian-Haʻole. Do I love one more over the other? The nation of Hawaiʻi will be restored through the Spirit of Aloha. We do not advocate violence. The ʻOhana o Hawaiʻi sees Hawaiʻi as the Aloha Capital of the World, a model for world peace.”

Through the 1980s, Aunty Peggy continued to assert Hawaiian independence and also advocated for religious freedom, arguing that Hawaiians had inherent rights to practice traditional cultural beliefs, rites and usage relevant to practicing our beliefs throughout the Hawaiʻi archipelago. She said that these rights existed since time immemorial and have never been extinguished, and filed documents to this effect with the United Nations and the International Court of Justice in 1980 and 1981. Aunty Peggy believed that the soul of Aloha rests in Nā ʻōiwi o Hawaiʻi and our culture gives it meaning. If we are to have peace in the world, we need to instill the Spirit of Aloha in our hearts and in our actions. She firmly believed that Aloha is Love, and God is Love. And she also preached that, should this Aloha continue to be threatened by United States, her Akua would send wrath upon those who brought death to Hawaiʻi and our Aloha.

Inquiries about Aunty Peggy and her life should be directed to Liliʻu Ross, email: liliuross[at]gmail.com

2013 Honorees

Henry Welokīheiakea‘eloa Niheu Jr.

& Dr. Richard Kekuni Akana Blaisdell

“He ʻaʻaliʻi kū makani mai au; ʻaʻohe makani nāna e kulaʻi”

Strong like the ʻaʻaliʻi in which no wind can knock it down

Henry Welokīheiakea‘eloa Niheu Jr., also known as “Kīhei” and “Soli,” was born in Honolulu. He began his activism began upon returning from his university studies at San Jose State and responding to a call from his Niʻihau ‘ohana to prevent the sale of the island. Learning much from the 1960s struggles of Native American, Black, Chicano and other oppressed peoples, Soli began to question the state of his people. Soli involved himself in the antiwar protests and the struggles for ethnic studies on the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa campus. He was a founder of Kokua Hawai‘i, a group that was influential in organizing against the evictions of Kalama Valley residents, actions that many mark as the birthplace of the Hawaiian Renaissance. Soli then became a lead member of HULI (Hawaiians United for Liberation and Independence) and consistently represented Ka Pae ʻĀina ʻo Hawaiʻi in the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement.

An international leader as well, Papa Soli traveled throughout Moana Nui, and stood side by side with sovereignty and independence leaders such as Oscar Temaru of Tahiti, and Titewhai, Hone, and Hilda Harawira of Aotearoa. Educated and articulate, Papa Soli spoke for the rights of all Indigenous people. Irreverent and hilarious, he wielded his malo like an ironic sword, mooning leaders of occupying nations throughout the world.

Close to his heart was work done with co-founder, Dr. Kekuni Blaisdell, on the convening of the 1993 Kānaka Maoli Tribunal, an international tribunal convened to investigate the role of the US in the overthrow. A father and grandfather, “Papa Soli,” as he is affectionately known, continued to fight for his people into the 2000s. He was a founding member of Hui Pū, a diverse coalition of Hawaiians who organized to protect self-determination and oppose the model of federal recognition that Nīheu and others believe is a sham of pseudo-sovereignty.

His staunch and unyielding belief in Kānaka Maoli independence put him at the vanguard of what people know as the Hawaiian sovereignty movement. Papa Soli was at the forefront of Hawaiian land and independence struggles for four decades, before passing into the realm of the ancestors on November 30, 2012. “Welo kīhei a ke Aʻeloa” (Cloak fluttering in the Aʻeloa wind)

Dr. Richard Kekuni Akana Blaisdell was a healer. His love for his family, and his prestigious medical career in hematology and pathology, were balanced and focused by his aloha ‘äina, his patriotic devotion to Hawai‘i. He explained that his name, Kekuni, passed down from his Maui lineage, suggested the position and responsibility bestowed upon him. Kuni, as it was explained, is a special fire ceremony associated with an ancient form of healing whereby a medical specialist, a kahuna kuni, would divine the circumstances of a particular illness, or even death, to properly treat the sickness or to determine the

responsible parties. In this respect, Kekuni Blaisdell’s legacy is one of diagnosing and problematizing the sickly condition of the Hawaiian people against a century of land displacement and American trauma, while at the same time restoring health and life, ea, to his beloved nation through his dedication to restoring independence to Hawai‘i.

Kekuni Blaisdell greeted every person he met the same way, with a glowing smile and a warm embrace. Uncle Kekuni always took the time to acknowledge everyone in the room. It was important to him. He embraced you with two hands and pressed his nose and forehead to yours to exchange a deep and long honi, the symbolic exchange of hä, or breath, which connects the lines of our shared past and binds us to a collective future. Uncle Kekuni always took a moment to inspect you, top to bottom, at which point he would give you his typical diagnosis: “Ikaika!”

Uncle Kekuni, as we affectionately called him, was known more widely as Dr. Richard Blaisdell, a pioneering hematologist since the 1940s. His work advanced the field of medicine in Hawai‘i, where he became a professor emeritus and first chair for the newly founded John A. Burns School of Medicine at the University of Hawai‘i at Mänoa. His work with survivors of the atomic attack on Japan, and his subsequent study on the health of Native Hawaiians in the 1980s, were central to his illustrious medical career.

Framed behind retro spectacles and a matching pocket protector for pens he always kept handy for note-taking, Kekuni was born of a different era. Although his daily attire may have hinted at his profession as a medical doctor and distinguished professor, I feel it was more a reflection of his refined character: always put together, always prepared, always well dressed. He wore pressed slacks, business shoes, and a neatly ironed aloha shirt, which he often covered with his famous black Ka Ho‘okolokolonui Känaka Maoli—The Peoples’ International Tribunal, Hawai‘i shirt he printed en masse as a means to promote and fund this international event in 1993. Uncle Kekuni wore those black shirts proudly everywhere he went. His attire became symbolic of his life, as his medical career began to be eclipsed by his growing sense of cultural and national identity. The shirts reflected his reclamation of who he was, but beneath the exterior still beat the heart of a healer. Wearing those shirts was his way of protesting American colonization while at the same time promoting self-determination and independence for Kānaka Maoli. It was his armor.

His education in America at the University of Chicago exposed Uncle Kekuni to the realities of racism and segregation. While he was in Japan, working with atomic blast survivors, his views on power and militarization underwent a major shift. His commitment to health, people, and service became even more politicized when he returned to Hawai‘i with his family during the period known as the Hawaiian Renaissance. In 1966, after twenty-two years away from Hawai‘i, Kekuni became drawn more and more to the resurgence of his culture, language, and history. He began to identify himself as Kanaka Maoli, the name for the true indigenous people who first settled Ka Pae ‘Äina, the Hawaiian Archipelago.

By the 1980s, Kekuni had fully embedded himself into Hawaiian culture and soon began to run with the independence crowd. He credited legendary icons of the Hawaiian movement, such as Kïhei “Soli” Niheu of the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement, Hawaiian filmmaker Puhipau Ahmad of Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina, and Imaikalani Kalahele, revolutionary artist and poet, as opening his eyes to the marginalization of Känaka in Hawai‘i. Kekuni gave recognition to these men over and over again for his colonial emancipation and for introducing him to the Hawaiian independence movement, which he quickly became a crucial part of.

I came to learn that the awakening of Kekuni’s Hawaiian consciousness, coupled with his prestigious medical career, helped to give the young and developing sovereignty movement serious traction and legitimacy in advancing the cause. Yet I pause to contemplate whether Kekuni himself would say otherwise—that it was his commitment to Hawaiian consciousness and activism that validated his medical work. Either way, the rebirth of Kekuni Blaisdell, the Kanaka Maoli patriot, and the resuscitation of ka Lä Ho‘iho‘i Ea (Hawaiian Sovereignty Restoration Day) in 1985, occurred during an era when Hawaiian independence was converging with a swelling interest in the revival of Hawaiian history, language, and culture. Standing at the center was Dr. Kekuni Blaisdell.

To read and download a collection of articles on Dr. Kekuni Blaisdell, click on this link:

http://www.kamehamehapublishing.org/hulili_11_2/